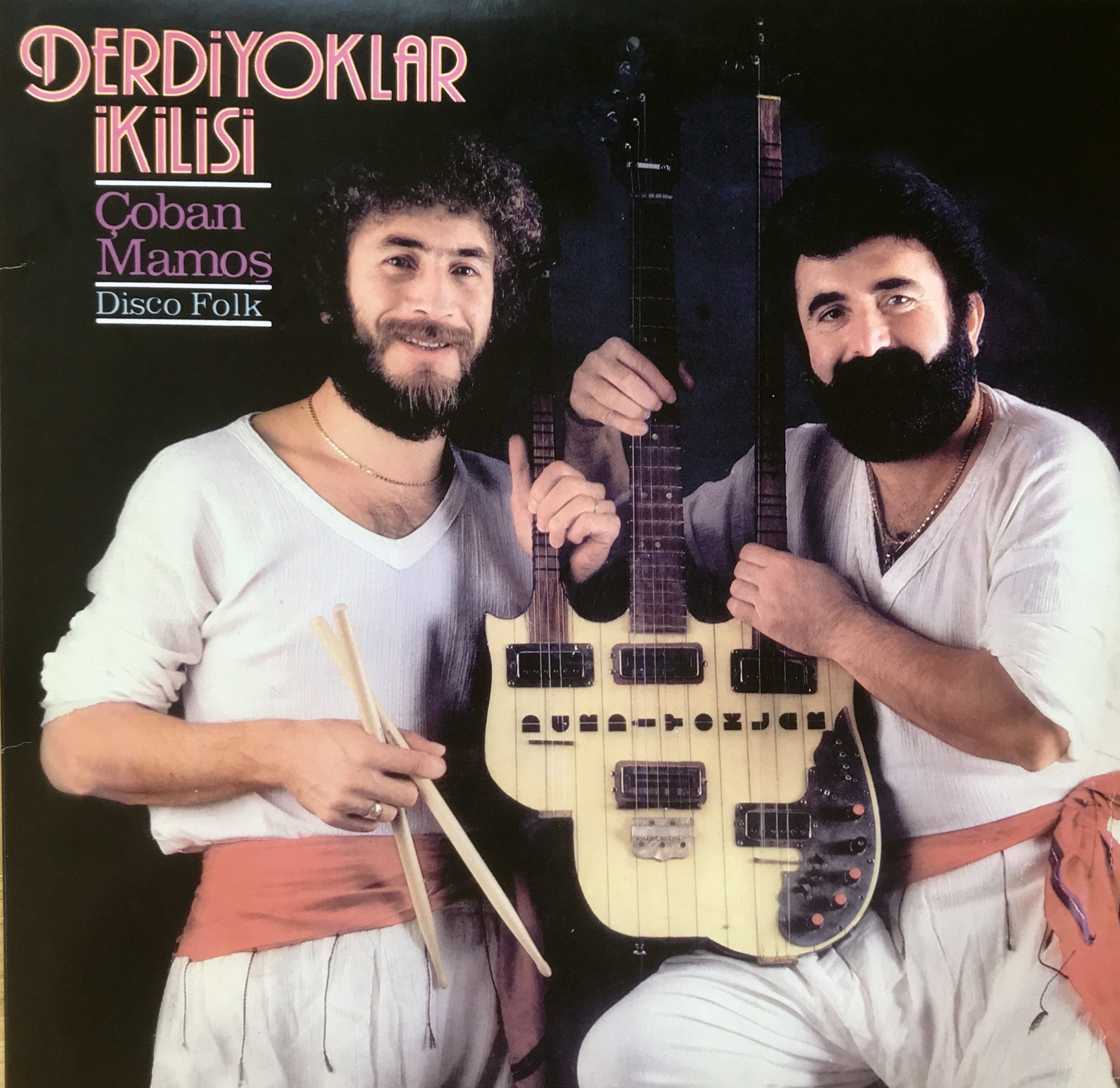

As Ali Ekber Aydoğan, more widely known as Derdiyoklar Ali, passed away on May 14th, we decided to publish our interview with him before planned. From the village in Malatya, to making music at weddings in Germany, we talked about his conception of his triple neck guitar and disco folk music out of his own unique poetry-interspersed language, enriched by anecdotes with Müzeyyen Senar and Neşet Ertaş...

Translated to English by Zeynep Beler.

The cover image is from the music video below, that was made in 2019 for the song recorded in the beginning of 80s, 'Liebe Gabi'.

We met Derdiyoklar Ali, on a video call on the 20th of April.

This meeting was set in motion by Istanbulberlin’s joint project with Nazlı Sağdıç Pilcz examining the reflection of guest workers’ stories in music, in recognition of the 60th anniversary of the worker migration from Turkey to Germany. Nazlı called me after the meeting, both of us feverish with excitement: “That was one of the most fascinating hours of our lives.”

Derdiyoklar Ali passed away on May 14th. He’d still had so much in the works for after the pandemic: celebrations in his home village, with the support of the Ministry of Culture, for his 50th year in the arts, a third book, a new album, international concerts…

Parts of our conversation had been harried by thoughts of death: his wish to be interred at his home village, the poems he read out loud to his iPad in case he died, his comment that “I might just leave this world too,” as we talked about the importance of paving the way for the young, his plans for a monumental tomb in his home village similar to that of Jimi Hendrix whom he’s often likened to, that would feature his triple neck guitar and help bring income to the village…

Derdiyoklar Ali lamented, “We opened up the Anatolian wedding tradition to the world. We introduced Arguvan folk songs to the world. There was only one oversight: our record company introduced us to the world but not to Turkey.” In the light of the deplorable development, we decided not to hold out on the publishing of this interview, with the intent that it serves as both a commemoration and an introduction for those not yet familiar with him.

We’ll look back on our brief acquaintance with the memory of his genuine, enthusiastic conversational style. May he rest in peace.

We had gotten ahold of old issues of Roll magazine, of which he spoke highly as, “It really has some excellent features!” in order to read the interview conducted with him at his village. Now his interview with Çiğdem Öztürk and Derya Bengi is available digitally. Readers interested in getting to know Derdiyoklar from a vantage point between Turkey and Germany can read Murat Meriç’s commemoration piece or listen to DJ Booty Carrell at bi'bak from here. The Elektro-Dschungel version of Liebe Gabi that is mentioned in the bi'bak interview is here. .

Disco-Folk

Derdiyoklar Ali is a contemporary bard who, as a witness to his times, believes it paramount to speak out on the truths in the daily agenda

We’ve given authentic, unadulterated renditions of folk music,” he explains his work.

His authenticity, however, became merged with his own style: the electric bağlama he played standing up and later, the triple neck guitar of his own invention, and his band’s dynamic stage performances “clad in Anatolian wool socks under salwars, with either sneakers or rawhide moccasins” that captivated audiences.

Dubbed disco-folk, this music and its execution was so ahead of its time that it could still speak to young people, internationally no less:

In 2018 or -19, I had a rock concert with youths in Berlin. They asked me, ‘We’re organizing an international only night. Will you come?’ They brought me in. It really was a gorgeous hall. Would you believe it, there were all of 50-60 Turks there. They’d made such a formidable organization, we all got so carried away, in that smoke, playing guitar and singing, it was incredible. I look across me and to the left are Japanese girls, crying, to the right German girls, also crying. They’re thinking I’m crying too - we sweat so much it looks like crying. And I do cry sometimes, when I sing, when I play.

Not only did he popularize the Anatolian wedding tradition throughout Germany but also inspired many musicians and paved the way for them to begin monetizing their music. His compositions were performed by the likes of Belkıs Akkale, Sebahat Akkiraz and Güler Duman.

His foreign adversaries bombed his home and his car was torn to pieces. He fought against them through his folk songs. What follows is the story of Ali Ekber Aydoğan, born in Malatya, Yazıhan's the Yukarı Tenci Obası of Fethiye Village, and his conception of disco folk out of his own unique poetry-interspersed language.

Troubled - Derdi Çok - Since Middle School

Influenced by the bardic tradition, Derdiyok Ali was writing poetry and composing songs as early as middle school. The kirve* affinity is an important institution in folk tradition that’s almost tantamount to fatherhood. Ali’s kirve was none other than the composer, poet and writer Âşık Mahzuni Şerif (1939 – 2002), renowned through folk songs such as “Çeşmi Siyahım” and “Dom Dom Kurşunu” and considered one of leading bards of the century. He told Ali that he would like “the Derdiçok name to be added to his own”, but soon after they learned of the existence of a 15th century bard with the same name. The opposite, “Derdiyok”, would receive Âşık Mahzuni’s blessing to be his pseudonym, never to be discarded. [*Kirve: A sort of godfather who usually takes on the financial cost of a boy’s circumcision and is tasked with holding him down and placating him during the procedure, thereafter gaining “parental rights” over the boy not dissimilar to those held by his actual father.]

Ali Ekber Aydoğan, Âşık Mahzuni Şerif ile.

Western Strings with Eastern Overtones

Partial to 7-inch records, he’d already learned as a child from mentors such as Fahri Kayahan to sing in time to the tambourine, accompanying them to play at weddings. Not much later, armed with his tambourine, he made his way to the definitive Plakçılar Çarşısı - record-company arcade - in Beyazıt, declaring that he wanted to make a record. When asked his musical style, he replied, “Drums in the foundation, electric guitar and electric "bağlama" tunes; Western strings under the surface with Eastern overtones, like a synthesis of the East and West,” this at a time Anatolian Rock as a genre did not yet exist. What Derdiyoklar Ali longed for, he told us, was to contemporize the bardic tradition and gain acclaim through modern music. He was brought into the studio with Cengiz Coşkuner on guitar. The Turkish folk music artist and bağlama virtuosi Arif Sağ, of "Seher Yıldızı" and "Mavilim Mavişelim" fame, was also present for the recording session of “Gurbet Treni” and came away impressed. And so was Derdiyoklar Ali’s inducted into the music market via his very first 7-inch record.

The Triple Neck Guitar a.k.a Derdiyoklar

During the 70’s, he was “spurred on by political dynamics” to travel to Germany to attend university. He was moonlighting as a musician at the time his friend İhsan Güvercin, whom he described to us as “supremely talented”, also arrived in Germany. They signed contracts with various casinos in ’76-77, with İhsan on bongo and Ali, standing up, on "bağlama".

After obtaining his musician’s residency permit, he returned to Istanbul and ordered a triple neck guitar from “Bağlamacı” Ragıp Usta which he then dubbed “Derdiyoklar”.

Long before they would be likened to the White Stripes, the Derdiyoklar Duo with their triple neck guitar and other guitar-like lutes soon became the most sought-after musicians at guest worker weddings in Germany.

Müzeyyen Senar: “Son, Come to Turkey”

In 1979, the Derdiyoklar Duo was scheduled to open for the Gurbet Kervanı Concert in Stuttgart that would feature a procession of performances from artists such as Özay Gönül, Erol Taş and Müzeyyen Senar. They performed to a rapt crowd, Ali said, and relayed the rest:

Here I am all beard and hair, triple neck guitar around my neck, and I hop off and go backstage. Müzeyyen Senar opened her arms to me: ‘Son,’ she said. ‘Who on earth are you,’ she said and embraced me hard. She wiped the sweat off my brow. ‘Son, you have to come, you have to come,’ she said. ‘Come to Turkey,’ she said. ‘What style! What music!’

I wish now that we’d listened to Müzeyyen Senar and went.

We didn’t, but those words of hers in ’79 nevertheless incited us. We went back and we said, all right, let’s put out a record.

“Barış Manço Took a Few Leaves Out of Our Book”

Though they didn’t return to Turkey, they maintained their cultural rapport with Turkey.

"Our work was all about voicing day-to-day, contemporary concerns. Derdiyoklar would be affected by something, say, we had our own shepherd, Mamoş the shepherd. We loved him, the man was 24-carat gold. So we would sing, `Mamoş the 24-carat shepherd` and Barış Manço took a few leaves out of our book, issuing a record soon after titled `24-carat Manço`. We wrote the song ‘Yaşayın Hayvanlar’ inspired by a folk idiom about donkeys and he went on to make ‘Arkadaşım Eşşek [My Friend the Donkey]’."

“Neşet Ertaş was very fond of my poetry”

“Neşet Ertaş was very fond of my poetry. Every time I read him one, he would ask: ‘Ali my boy, have you ever been in love?’ What of love, I would say. ‘Heaven’s sake, how do you write without being in love? I was in love with Leyla,’ he would say, and what works he put out during that time.

“In fact I wrote a fine poem inspired by his words, which I also read to him:

Is desire summertime or a sum of money? I know not, tell me if you do. Is love real or a sum of money? I know not, tell me if you do. I ran into love but she didn’t return my greeting She passed me by, her eyes never saw me A hot-blooded Majnun disregarded I know not, tell me if you do. I am Derdiyok, death has summoned me Other days, it was my rose that called me Why has my hair turned gray overnight? I know not, tell me if you do.

Arif Sağ: “Watch out for these two shagrags”

In 1964 Arif Sağ, whom they’d met earlier, sent them to Türküola, the record company founded in Cologne in 1964 and set up shop in Unkapanı in 1973 that was behind the majority of Turkish albums produced at the time, along with a note reading “Watch out for these two shagrags, don’t you let them get away.” Once their cassette came out, they were thrust “smack into the middle of Europe’s agenda”. Ali added, “It’s sensational, our records are selling millions of copies.” However, he went on to explain, they had a ten cassette deal and İhsan Güvercin left the band after the seventh, after which Derdiyoklar Ali kept going with Mehmet Tanış, with whom he would play for the next twelve years, to complete the contract. In fact, they would go beyond their word and make two more albums.

Ali Ekber Aydoğan and Mehmet Tanış

In fact, they would go beyond their word and make two more albums. “Then we went on to perform these pieces on TV and shoot videos for them. Long story short, we’ve kept going the same way ever since.

“Let me read you one of my latest pieces:

For 50 years I play the lute, I never harmed a string. I searched for water in the desert, I never harmed the desert, Nor have I harmed the lake. The winds of desire blew, The bee alighted on my blossom, My home is afield, I never harmed another I never harmed a word I played my tears in chords I longed for my village some I awaited by the path for a friend I never harmed the path. I never harmed the village. My companion he suffers Peace, with love sows Ever I have fought against the thorn Yet I never harmed the rose. I never harmed the honey. Derdiyoklar yet I am troubled This heart that the arrow touches. The way of the people is my prerogative I never hurt a creature I never hurt a thing. I never hurt you.

[…] yolunu açtı. Derdiyoklar Ali ile vefatından önce gerçekletirdiğimiz röportajı buradan […]